Memento Mori

- Joel McFarlane

- Jun 10, 2022

- 26 min read

“Memento Mori.”

A vacant-eyed skull grinning

at the passers-by.

Death does not mar the party.

He celebrates New Year too.

“Entering the realm of the Buddha is easy, entering the realm of the Devil is difficult.”

New Years Day, Kyoto, Japan. The medieval city is bustling. Laughter, chattering, movement, colour. A blind masseuse in rags blowing his whistle. A small group of monks, on pilgrimage, carrying staffs and wearing dark robes, the blue stubble on their heads begging for the razor. The city’s inhabitants have long since performed Oshogatsu, the traditional rites of deep cleaning—tidying their homes, beating out their tatami mats, tossing out the old in preparation for the new. Dazzling women throng the streets: their faces powdered white, wearing colourful kimonos, the scent of fresh flowers trailing them wherever they go. Naturally, close on their heels, the men follow. Fresh-faced, their hair tied into top-knots, they pursue the women’s scent like hunting dogs. Jostling each other, the men laugh and gesture at the prettiest specimens. Playing coy, the girls giggle behind their long sleeves and totter on their timber geta sandals.

In front of every shop and home hang the ubiquitous Shimekazari—New Years decorations made of rice, straw rope, pine branches and folded paper. Before the more stately homes, Kadomatsu shrines, built of pine, bamboo and plum trees, have been erected as dwelling places for the gods in the hope they will visit to bless the home’s inhabitants.

Yes, the fickle gods. Who can scrutinise their ways? After so many years of civil strife the New Year promises a fresh start. Across the nation, it’s everybody's birthday and the simmering atmosphere complements this fact. The wealthier classes rush past, hidden inside their palanquins, carried by sweaty men in straw sandals caked with mud. The nobles, seated in coaches drawn by oxen, move down the avenues accompanied by warriors on horseback, the arrows in their quivers rattling and their steads exhaling clouds of mist. Princes, paupers, peasants, prostitutes—you name it—now clog the streets. All classes of people flowing in different directions. Many of them heading towards the nearest shrine or temple to perform the traditional rites of Hatsumode. Others returning from the same temples, smiling now, having unburdened themselves to the gods.

And it’s just outside one of these temples that a group of women start shrieking. Dressed in finely embroidered silks, they stumble backwards in horror, muddying their expensive sandals in their retreat. A strange monk wearing a crazed grin blocks their path. He wields a bamboo pole with a human skull stuck on the end, its dirty black eye sockets staring back at them.

“Beware, beware!” he yells, shaking the sacrilegious object at them.

The skull's jaw, hinged with straw, moves up and down as he shakes it, as if it were echoing his strange words. He advances on the group, bringing the skull almost close enough for one woman to kiss. Recoiling, her shrieking only makes him laugh more.

“Look!” he laughs. “Behind all that make-up, below the flesh, you’re all one and the same.”

Intervening, the women’s servants rush to the front. The hardy men, their sleeves rolled up, immediately recognise the dishevelled man breathing saké fumes into their faces.

“Ikkyū!” the headman yells. “What is this scandalous behaviour?”

Oh yes, they recognise him alright. His reputation precedes him. The self-described Crazy Cloud, Ikkyū Sōjun. The monk rumoured to be the bastard son of the Emperor, but who now lives as a vagabond, carousing with prostitutes and drinking without shame. Some say he is a Zen master, others that he’s a demon. It’s even whispered that he doesn’t just break the monk’s precepts against saké and sex, but that he eats animal flesh as well.

“Ikkyū!” the headman continues. “Why do you want to spoil the holiday like this?”

Grinning, Ikkyū thrusts the skull forward, saying, “Reminders of death should not mar the celebration.” And breaking into a dance with his empty-eyed friend, he sings, “Look, I am celebrating too.”

“The Lotus flower is not stained by the mud.”

Ikkyū Sōjun (1394 - 1481) defies easy description. No Western equivalent exists to whom one might make a comparison. He was a poet, philosopher, iconoclast, rebel, calligrapher, painter, tea master, flute player, avant-gardist, sex fiend and Zen master. And even that barely scratches the surface. One moment, dressed in the finest monk’s regalia, he was keeping company with Shoguns and Emperors, writing the most profound Zen poetry ever penned. The next moment, he was begging in the streets dressed in rags, scribbling poems glorifying whores and celebrating the virtues of drunkenness. Upon his appointment as abbott of Nyoi-an, a sub-temple of Japan’s greatest temple Daitoku-ji, he barely lasted a week before he resigned in disgust, leaving a pointed poem behind as a final insult,

Ten days in this temple and my mind is reeling!

Between my legs the red thread stretches and stretches.

If you come some other day asking for me,

Better look in a fish stall, a saké shop, or a brothel.

Clearly, a man who didn’t mince words or play by the rules. Picture a Pope renouncing the papacy and fleeing to the red light district to find his spiritual path amongst whores and gamblers. Well, that’s Ikkyū Sōjun. The final line of this poem is a splendid exclamation point—a three-fold middle finger to the Buddhist establishment of which he was considered by many to be its greatest practitioner. Indeed, he couldn’t have been any clearer. Three heresies, bullet-pointed, one after the other: animal flesh, alcohol and sex. A direct rebuke to the hypocrisy of the religious authorities whom he resisted his entire life.

Imagine Diogenes, Saint Francis, Caravaggio, Francois Villon and the Marquis de Sade were all one and the same person. You’d still barely hit the mark. One story has it that while staying in Sakai, he wandered around town with a wooden sword wherever he went. When confronted with the charge, “Swords are for killing people and are hardly appropriate for a monk to carry.” He simply replied, “As long as this sword is in the scabbard, it looks like the real thing and people are impressed, but if it is drawn and revealed as only a wooden stick, it becomes a joke—this is how Buddhism is these days, splendid on the surface, transparent inside.”

A timeless statement, no? An apt analogy for all religious establishments, regardless of the culture, climate or continent.

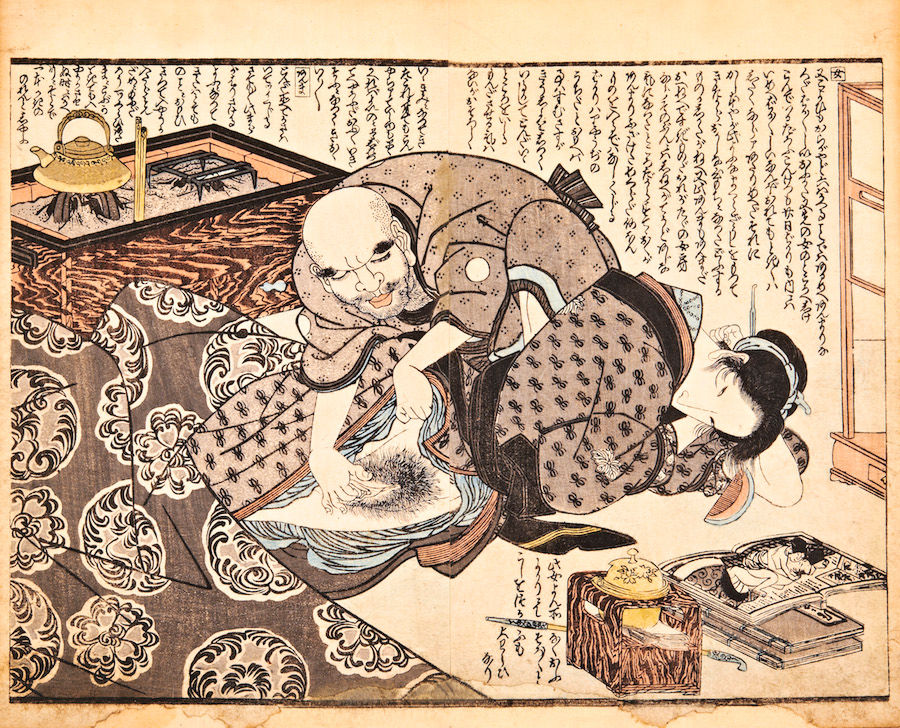

No doubt, his open-mindedness knew no bounds. Despite the celibacy celebrated by most of his fellow monks, he gloried in its opposite. Often led by that infamous “red thread”, he felt not a hint of shame in it. In his mind, sexuality wasn’t to be frowned upon. If anything, it was to be enjoyed first, and then, if the mood took him, immortalised in verse. Countless examples of his sexual poetry remain. For some, his reputation rests on these poems alone. Not that his freedom-loving verses are restricted to sex, or even heterosexual sex for that matter.

Exhausted with homosexual pleasures, I embrace my wife.

The narrow path of asceticism is not for me;

My mind runs in the opposite direction.

It is easy to be glib about Zen—I'll just keep my mouth shut

And rely on love-play all day long.

Certainly, while treating Zen Buddhism as a life or death matter, Ikkyū Sōjun had no time for superficialities or frivolous regulations. It was the blood of religion that mattered to him most, not its theories or its accoutrements. In his mind, a pious monk sequestered in a drab temple, hidden away from society and temptation, was a fraud worse than hell itself. The true goal, as far as he was concerned, was finding one’s enlightenment in the street in direct relation to life and society. Amongst fishmongers, beggars, streetwalkers, and scoundrels he tested his mettle and found his milieu. As the following two poems attest, enlightenment was just as likely to be found in the hole between a woman’s thighs as it was in reading the holiest sutras.

Follow the rule of celibacy blindly and you are no more than an ass.

Break it and you are only human.

The spirit of Zen is manifest in ways as countless as the sands of the Ganges.

Every newborn is a fruit of the conjugal bond.

For how many eons have the secret blossoms been budding and fading?

With a young beauty, I am engrossed in fervent love-play; We sit in the pavilion, a pleasure girl and this Zen monk. I am enraptured by hugs and kisses And certainly do not feel as if I am burning in hell.

A sex-loving monk, you object!

Hot-blooded and passionate, totally aroused

But then lust can exhaust all passion,

Turning base metal into pure gold.

The lotus flower Is not stained by the mud; This dewdrop form, Alone, just as it is, Manifests the real body of truth.

“An evil devil with piercing eyes that see as clearly as the sun and moon.”

Indeed, not long before that other famous medieval poet and vagabond, Francois Villon, was born in France, Ikkyū Sōjun crawled out of his mother's womb in Kyoto, Japan, in the year 1394. And with this, the man’s legend was born. Said to be the son of the Emperor Go-Komatsu, his mother, a low-ranking court noblewoman, was cast out of the capital at the behest of the jealous empress. Forced to flee to Saga, Ikkyū was raised until he was five by servants and then placed in a Zen temple for his own safety. A smart move given the politics of the age. In such violent times, being a distant heir to the throne, even one born to a lady-in-waiting, was sufficient reason for powerful people to consider plotting the boy’s murder.

And so the bright-minded brat began his journey to greatness. Some might even say it was written in the stars. Right from the start, Ikkyū showed himself to be cut from uncommon cloth. Perhaps it was his royal blood or else a favour from the gods, but even as a child his reputation was one of an extraordinary intellect coupled with a precocious rebelliousness. As an acolyte at the temple, Ankoku-ji, he studied the Buddhist scriptures and the classics of China and Japan where he fast proved himself a brilliant student. The child prodigy even attracted the attention of the Shogun, Yoshimitsu, who summoned the boy to his castle for a personal audience.

However, it soon became apparent that temple life was not for Ikkyū. At sixteen years of age, appalled by temple politics and the hypocrisy he witnessed there, the boy had finally had a belly-full. Not even his homosexual dalliances with fellow monks could keep him from fleeing. So, with this in mind, the teenager left in disgust, announcing his departure in his usual trademark style,

Filled with shame, I can barely hold my tongue.

Zen words are overwhelmed and demonic forces emerge victorious.

These monks are supposed to lecture on Zen,

But all they do is boast of family history.

Never one to take the easy route to enlightenment, he started training with an eccentric old monk, Ken’ō, in a ramshackle hut in the hills outside Kyoto. His master, an outcast from the Zen establishment, suited his lone disciple fine. Maybe the old man recognised his own rebelliousness in his precocious young underling. There’s no doubt that Ikkyū preferred the old man’s demanding teachings to the relative comforts of the temple he’d resided in for the previous decade. Nonetheless, given Ikkyū’s character, one may wonder . . . on lonely evenings, as the rain dripped in through the leaky roof, did he long for the warm flesh of one of his fellow monks so as to satisfy that famous read thread stretching out between his thighs? At the same time, he also studied literature with a scholar monk at a nearby temple. As legend has it, it was at this very temple that the new Shogun, Yoshimochi, visited to demand a scroll that was in the temple’s library. As the other students trembled in fear at the most powerful man in the nation, Ikkyū didn’t flinch. Bringing out the scroll for the Shogun, he refused to step down into the entrance hall as etiquette demanded. Instead, he faced the nation’s leader from on high without bowing or lowering his eyes. Staring down the man who could have had him beheaded, until the Shogun finally stepped forward and snatched the scroll from the teenager’s hands. Was it courage, stupidity, or simply a suicidal desire that made him risk his neck so recklessly? We can only hazard a guess. But at this stage in his life, Ikkyū’s writings clearly attest to a deeply felt Buddhist pessimism and a tendency towards more melancholy musings. Nevertheless, he remained with his master, Ken’ō, for another four years. And there they stayed until the old monk finally passed away when Ikkyū was 20 years old. Having acted as the old monk's sole gravedigger and mourner, there’s no surprise he fell into a suicidal depression in the period that immediately followed.

His mind fractured at the loss of his master, he set himself on committing suicide in Lake Biwa, saying, “If I am useless here on earth, at least let me be good fish-food!” But thankfully, a letter from his mother gave him pause. She wrote, “Enlightenment will be your’s one day; please persevere.” And so he did, finding a position with the much revered master, Kasō, a man even more severe than Ken’ō. Unsurprisingly, when he presented himself at the master’s retreat, he was refused acceptance. Ken’ō had no time for the weak-willed wastrels who normally pestered his door. And yet, undeterred, Ikkyū wouldn't budge. He was no ordinary wastrel. Despite the gatekeeper beating him and dousing him with food scraps, he persisted for five days straight until he was finally granted entrance.

As one might expect, residing at Kasō’s was no cake-walk. But then, Ikkyū was no everyday acolyte. Daily life at the monastery consisted of heavy labour, meagre food, and hours of arduous meditation. However, in spite of his freedom-loving ways, and even his distaste for authority, when it came to Zen, Ikkyū was no dilettante. He recognised a real master. And he was resolved to reach enlightenment, no matter the personal cost.

It would take another six years being baked in Kasō’s kiln, before his efforts paid off. One evening, while meditating on a boat drifting in the middle of Lake Biwa, a crow cried out overhead. And it was at that moment that everything became clear to the young man. In an instant as infinitesimal as an atom, he was born anew, and he rushed back to the temple to describe his experience.

In true Zen fashion, his master, Kasō, mocked him for his presumption. “You may be an Arhat,” he laughed, “but you are still no master!” And naturally, Ikkyū couldn’t have cared less what the man said. “Being an Arhat is fine with me.” he scoffed. “Who needs to be a master?” To which, Kasō replied, “Then you really are a master!” Indeed, it was just as is his mother had written. “Enlightenment will be your’s one day.” And so it was. When the master asked for the customary enlightenment verse, Ikkyū brushed the following, For twenty years I was in turmoil Seething and angry, but now my time has come! The crow laughs, an arhat emerges from the filth, And in the sunlight a jade beauty sings!

“A Crazy Cloud, out in the open!”

Newly minted and enlightened, Ikkyū remained with Kasō for several more years. There’s no doubting his devotion to the old man. He even cleaned his master’s excrement with his bare hands when the old man, sick with diarrhoea, soiled himself. And thankfully, in spite of the young man’s increasingly outrageous behaviour, Kasō recognised the young man’s promise. Once, when Ikkyū appeared wearing rags at the memorial service for Kasō’s master, Kasō was heard saying, “Ikkyū is my true heir, but his ways are mad.”

And mad he most certainly was, or at least according to conventional standards. But then, perhaps this madness was Ikkyū’s true genius. After all, in a stratified nation on the cusp of a civil war that would last 148 years, his behaviour simply highlighted the insanity and hypocrisy bubbling underneath the veneer of respectable society. With its bankrupt nobles, warlords vying for influence, fading Shoguns, scheming monks and starving peasants, the nation was fast rotting away beneath its finely embroidered facade. A close reading of Ikkyū’s verses certainly leads one to ask if the mad monk wasn’t in fact the only sane man left in Japan.

As Friedrich Nietzsche wrote, “In individuals, insanity is rare; but in groups, parties, nations and epochs, it is the rule.” And in that chain of islands clogged with conformity, Ikkyū’s individuality was as rare as European glass. In fact, one could imagine Ikkyū himself brushing Nietzsche’s very words in his now priceless calligraphic script.

And as fate would have it, it was just as Nietzsche wrote elsewhere, “One repays a teacher badly if one always remains nothing but a pupil.” And so, after an irreparable falling out, the teacher and pupil finally parted ways. The time had come for Ikkyū to strike out on his own, now a budding master in his own right. Even a man of Kasō’s caliber couldn’t fully comprehend, let alone excuse, Ikkyū’s wild ways. His troublesome student spending his days in formal Zen training at the temple, and his evenings in town, practising his own brand of heretical Zen. Frequenting bars and brothels, Ikkyū found more insight in the muck and mire of a sinful society than he did cloistered inside a temple of conformist monks. And by now, the two men, in spite of their respect for one another, were no longer capable of mutual coexistence. So, in 1426, Ikkyū finally strolled out the gates of Kasō’s retreat. The two men would never see each other again, that is, until Ikkyū briefly returned for the great man’s funeral.

By now, Ikkyū was 32 years old, and at last, as they say, the Crazy Cloud was born.

A Crazy Cloud, out in the open, Blown about madly, as wild as they come! Who knows where this cloud will gather, where the wind will settle? The sun rises from the eastern sea, and shines over the land.

From now on, Ikkyū would flow with the tides rather than follow any single regime. The wind blowing him where it will. His newfound peripatetic lifestyle dictated by his whims alone. No longer would his masters be severe old men or “profound sutras.” Instead, he read “the love letters sent by the wind and rain, the snow and the moon.” He found his wisdom in “a solitary tune by a fisherman” or the moans of a courtesan in the pleasure quarters. As far as he was concerned, the monks could keep their temples, rituals, timetables and their foul smelling incense. From now on, he would live as a vagabond, wandering here and there from Kyoto to Osaka, and Nara to Sakai. His incense would be the streets themselves, his mountain retreats, and the scent emanating from his lovers’ nether regions. The idols he bowed to now were made up of saké jars, a sparrow, a meal of octopus, another poem, a muddied street-side shrine, and most importantly, that “original mouth” that spoke so succinctly to him.

Yes, in the poem titled, A Woman’s Sex, Ikkyū spoke more living truth than a thousand moth-eaten sutras.

It has the original mouth but remains wordless;

It is surrounded by a magnificent mound of hair.

Sentient beings can get completely lost in it

But it is also the birthplace of all the Buddhas

of the ten thousand worlds.

Just as in another poem he immortalised its counterpoint, in a gem titled, A Man’s Root.

Eight inches strong, it is my favorite thing;

If I'm alone at night, I embrace it fully.

A beautiful woman hasn't touched it for ages.

Within my loin cloth there is an entire universe!

“The wild ways of the Crazy Cloud will never change."

Before the Romantics, the poète maudits, the Beats, punks, hippies, queers and even the Hip-Hoppers, there was Ikkyū Sōjun. The tepid rebellions of our contemporary equivalents are all but pale shadows of the man. This was a fellow who put his life on the line every single day, who strolled through mountains filled with brigands, who begged in the streets to survive, who often lived out in the open, who wrote poems for the lower classes in exchange for a spot of soy sauce, and who openly mocked the powerful. And all this by choice and design rather than necessity. Indeed, circumstances played no part in his choices. He could have possessed all the superficial trimmings of success had he chosen them. Having played by the rules, he could have become abbott of Daitoku-ji (a position equivalent to the Pope) and lived in the utmost luxury. But not Ikkyū. No, instead, the Crazy Cloud risked everything to live as an authentic human being. Experiencing every single day balanced on the razor's edge in between life and death, his vision never faltering, always seeking to deepen his path.

Naturally, no mediocre essay can capture the man’s essence, nor this small selection of his poetry. One must delve into his entire oeuvre to catch an honest whiff of the man who breathed such life into his every action and his every written word.

Forests and fields, rocks and weeds—my true companions. The wild ways of the Crazy Cloud will never change. People think I'm mad but I don't care: If I'm a demon here on earth, there is no need to fear the hereafter.

Indeed, how can one not admire this delightful demon? The more one reads his verse, his biography, and the historical conditions of the time, the more one marvels at the his clearsighted vision and the naive courage with which he confronted the world. This isn’t a time of welfare states, an age where people lived off government handouts. This is a turbulent time where abandoned babies were found dead on roadsides, where the samurai could cut down a peasant on any pretext, where even the monks’ morality was little more than an act. This is a time of war, famine, plague, rice riots and at times, localised holocausts. In our beleaguered west, we might bemoan our current economic disparities, but Ikkyū lived through the Ōnin War and witnessed the outright destruction of an entire city. The nation’s capital, Kyoto, gradually reduced to ash and rubble in the power struggles between the Hosokawa and Yamana clans. One of the greatest cities ever constructed by man, wiped off the face of the earth in a conflagration of fire, arrow, spear and sword. And throughout it all, both Ikkyū’s behaviour and his brush were pointed accusations at all humankind.

Human beings are indeed frightful beings.

A single moon

Bright and clear

In an unclouded sky;

Yet still we stumble

In the world’s darkness.

Clearly, this wasn’t some middle class, James Dean rebellion or that of a university student playing at Che Guevera. This was a rebellion of the heart and soul, the body and the mind. This was a rebellion with real risks and real repurcussions.

When the farmers were being bled dry by excessive taxation, he sent protest poems to the authorities without a single thought for his own neck.

Robbers never strike at the homes of the poor; Private wealth does not benefit the entire nation. Calamity has its source in the accumulated riches of a few, People who lose their souls for ten thousand coins.

Over and over, Taking and taking From this village: Starve the farmers And how will you live?

Indeed, while his fellow citizens sat snug indoors during winter, finding safety in the routine yet humdrum life, Ikkyū roamed the city streets and the mountain highways forever seeking freedom and enlightenment. Sometimes, he would starve for days on end or else find himself soaked to the bone by the rain, his straw sandals snapping in the cold so that he was forced to walk barefoot.

Woodcutters and fishermen know just how to use things. What would they do with fancy chairs and meditation platforms? In straw sandals and with a bamboo staff, I roam three thousand worlds, Dwelling by the water, feasting on the wind, year after year.

My real dwelling Has no pillars And no roof either So rain cannot soak it And wind cannot blow it down!

Of course, in our stable, prosperous times, it’s easy to be flippant when considering his lifestyle, but ask yourself, would you have the courage to throw all caution to the wind and live in such a fashion? Your next meal never guaranteed, your bed for the night the frozen forest floor, not a single coin in your pocket nor a friend for company. Would you choose to wear tattered rags for clothes instead of $200 sneakers and goose-down jackets so as to keep out the cold? Would you risk execution in support of the poor? Could you maintain your confidence, not to mention your sanity, never knowing where the next meal was coming from or whether or not the man around the next bend would give you some bread or else a blade for your belly?

Ikkyū had no such qualms. It wasn’t that he didn’t value his life. Quite the opposite. He held his life in such high esteem that living with less freedom than an animal was anathema to him. He looked to the birds, flying free, leaving not a trace in the sky behind them. He recognised that all the social codes were little more than fancy-dress, and that authority was nothing but an arbitrary twist of fate. His spirit had revolted against such things ever since he was a boy. Adult hypocrisy around every corner. Adult ignorance, or even lies, hiding behind nearly every single word they uttered. Indeed, he saw through the creature comforts of so-called civilisation. The prison bars of society and culture didn’t fool him. Better to die a free man than live as a slave to mediocre minds. And so he lived more freely than most civilised men before him. Strolling through slums and bandit-infested forests without weapon or support. Putting his trust in his destiny no matter where it might lead him.

Once, on a mountain path, he was confronted by a burly ascetic who demanded to know, “What is Buddhism?” To which, the middle-aged monk replied, “The truth within one’s heart.”

The brute, snickering at the monk’s reply, took out a dagger, and pointing it at Ikkyū’s chest said, “Well then, let’s cut out yours and have a look.”

And in typical fashion, without fear or hesitation, Ikkyū countered with a poem.

Slice open the Cherry trees of Yoshino And where will you find The blossoms That appear spring after spring?

“The road I travel is hard, so hard, and I know every step.”

For over 50 years, Ikkyū roamed Kyoto practising his own brand of Zen. “In the Mountains by day, in the city by night.” The mountains, where he meditated on nature and befriended the birds and flowers. In the city, where he drank saké and slept with prostitutes, often paying his way with his much sought-after poems and illustrations. Many of his fellow monks renounced him for his behaviour and he fought against them his entire life. Regardless of his penchant for solitude, his reputation brought him many followers, including monks, artists and poets. And yet, he also had a tendency to give them slip whenever the mood took him.

I like it best when no one comes, Preferring fallen leaves and swirling flowers for company. Just an old Zen monk living like he should, A withered plum tree suddenly sprouting a hundred blossoms.

At times, he lived on the streets or in the forests. Other times, he settled down for longer periods in mountain retreats, living as a hermit. But wherever he went, from the high to the low, paper and ink were his constant companions.

Bliss and sorrow, love and hate, light and shadow, Hot and cold, joy and anger, self and other. The enjoyment of poetic beauty may well lead to hell. But look what we find strewn all along our path: Plum blossoms and peach flowers!

Indeed, even with so many mistresses, poetry remained his one great love. It acted on him like magic. A dozen black characters on a sheet of paper sufficient to awaken a thousand impressions. Many theologians argued that monk’s shouldn’t dabble in such frivolous pursuits. And yet, on the other hand, many monks pursued the brush for the sake of fame and reputation. Two viewpoints, mind you, that were as foreign to Ikkyū as the thought of renouncing saké and sex. No, for him, poetry was a window into life completely intertwined with the deepest Zen philosophy. He had no time for clever wordplay, art for art’s sake, or poetry as pastime. In the Crazy Cloud school, the Zen poem was a direct tool capable of penetrating the deepest truths. Monks these days study hard in order to turn

A fine phrase and win fame as talented poets. At Crazy Cloud's hut there is no such talent, But he serves up the taste of truth As he boils rice in a wobbly old cauldron.

I don’t believe this avowed lack of talent was an attempt at false humility. Not at all. On Lake Biwa, all those years ago, while hearing a crow cry out, the last dregs of his ego had evaporated into the cold night sky. He didn’t write for fame. He wrote to express himself, to marvel at the world, to penetrate more deeply into life. At first glance, especially in the eyes of a westerner, his vision may seem gloomy, even nihilistic, but after deeper contemplation, one recognises the man's innate love for life. He once wrote, “Joy in the midst of suffering is the mark of Ikkyū’s school.” and his poems speak to this fact. If anything, Zen is a clearsighted view of existence that refuses the balms of blind positivism or false hope. It is an attempt at seeing the world as it is, without judgements, living without the delusions of the mind muddying the waters.

The vagaries of life,

Though painful,

Teach us not to cling

To this floating world.

Of course, one cannot discuss Ikkyū without discussing his love of sex. And certainly, while he may not be the first man to enjoy such pleasures, the verses he wrote celebrating it are often mistaken for mere erotica. Nothing, of course, could be further than the truth. As with everything he put his mind to, he brought to the enjoyment of sex a deep sensibility and a simple childlike joy. His contempt for the social rules that muddied the most beautiful aspects of life only drove him to sing its praises even louder.

Linji’s disciples never got the Zen message, But I, the Blind Donkey, know the truth: Love play can make you immortal, The autumn breeze of a single night of love is better than a hundred thousand years of sterile sitting meditation.

Indeed, if the sterile sutra’s were all but fingers pointing to the moon, then, for Ikkyū at least, sex was the moon. One can read about Zen all one likes. One may accumulate theoretical knowledge. But then, knowledge and knowing are two different things. Reading about enlightenment and experiencing enlightenment is the difference between reading a description of a meal and actually eating one.

Stilted koans and convoluted answers are all monks have, Pandering endlessly to officials and rich patrons. Good friends of the Dharma, so proud, let me tell you, A brothel girl in gold brocade is worth more than any of you.

Yes, and when he wasn’t singing love’s praises, Ikkyū was regularly decrying the falsehoods of his fellow monks. Accusing them with poem after poem. Reminding them time after time that formal Zen and religious ritual were as lifeless as a corpse.

Who needs the Buddhism of ossified masters? Me, I've spent three decades alone in the mountains And solved all my kōans there, Living Zen among the tall pines and high winds.

Who can really say what forces gave birth to the characters his brush traced across the paper? Having penetrated the illusion of the self, he didn’t take any credit for the poems that, even now, still cut through life to reveal both its entrails butthe mystery underlying it too. Don’t be mistaken. In spite of his joy at life, he also felt the deep tragedy of his existence. And as he aged, spending more time alone in the mountains and less time carousing in town savouring “whorehouse joy”, his poems grew more melancholy, more bittersweet, more contemplative.

Shut up in a hut chanting verse beside a single lamp; A poet-monk just follows nature without a set path. The advent of spring lifts my melancholy a bit, but the night is still so chill, Freezing even the plum blossoms on my calligraphy paper!

A thatched hut of three rooms surpasses seven great halls. Crazy Cloud is shut up here far removed from the vulgar world. The night deepens, I remain within, all alone, A single light illuminating the long autumn night.

“Long green sprouts, verdant flowers, fresh promise.”

There’s no doubting Ikkyū's decision to live as a hermit was a difficult one. Even being a master, his life in the mountains wasn’t some Buddhist fantasy where the master overcomes all suffering. Not in the slightest. Countless poems bemoan his daily difficulties as well as they glorified his short-lived pleasures. However, later in life, his verses start to address his advancing years, his loneliness and his growing lack of intimacy and sexual pleasure. My life has been devoted to love play; I've no regrets about being tangled in red thread from head to foot, Nor am I ashamed to have spent my days as a Crazy Cloud. But I sure don't like this long, long bitter autumn of no good sex!

For ten straight years, I reveled in pleasure houses.

Now I'm all alone deep in the dark mountain valley.

Thirty thousand cloud leagues live between me and the places I love.

The only sound that reaches my ears is the melancholy wind blowing in the pines.

Just picture this old monk, high in the mountains, alone in the fog and rain, meditating in his little hut. A small oil-lamp illuminating his writing paper. His skeletal frame trembling as he dips his brush into the ink with tears streaming down his cheeks. A man of blood and bone, and yet, a living ghost as well, traveling to and fro between the two worlds. Outside, the crickets play a simple tune that sometimes eases and other times, exacerbates, his melancholy solitude. Often unable to afford real tea or rice, he drinks citrus-rind tea and coarse millet instead.

With this in mind, one can easily imagine his joy when, at 77 years of age, he encountered a beautiful blind minstrel by the name of Mori. She was 30 years his junior and their meeting fast developed into a six-month love affair that is still celebrated in Japan today. Even being a so-called master, I suspect he couldn’t believe his luck. The dryness of his poems before their meeting fast became kindling for the fires of their passion and the timeless poems that followed. Indeed, reinvigorated by their time together, the verses now poured out of Ikkyū at an incredible rate. Verses that celebrate the joys of erotic intimacy in a manner still relevant over five centuries later.

The perfume from her narcissus causes my bud to sprout, sealing our love pact. The delicate fragrance of the flower of eros. A waterborne nymph, she engulfs me in love play, Night after night, by the emerald sea, under the azure sky. He brushed so many poems immortalising their brief dalliance, it’s impossible to select just one that fully captures the feelings he had for her. I can only hope that the few that follow reveal the essence of these brief but magical moment in the old monk’s life. I am infatuated with the beautiful Mori from the celestial garden. Lying on the pillows, tongue on her flower stamen, My mouth fills with the pure perfume of the waters of her stream. Twilight comes, then moonlight shadows, as we sing fresh songs of love.

The tree was barren of leaves but you brought a new spring. Long green sprouts, verdant flowers, fresh promise. Mori, if I ever forget my profound gratitude to you, Let me burn in hell forever.

Ah yes, the barren tree had sprouted new leaves alright. A tree that he feared had withered away, had burst back into life again as if by some miracle. And where so many monks had failed, by now, Ikkyū had addressed the problem of the “red thread of passion”. Rather than ignoring it, as most had done before him, or else resisting it with lifeless celibacy, he had fully confronted the famous sex kōan posed by the 12th century Chinese master, Shung-yüan.

In order to know the Way in perfect clarity, there is one essential point you must penetrate and not avoid: the red thread of passion between our legs that cannot be severed. Few face up to the problem, since it is not at all easy to settle. But you must attack it directly, without hesitation or retreat, for how else can liberation come?

“My skeleton exposed for all to see.”

Ever the contrarian, one of the strangest developments in Ikkyū’s story came about in his final years. Just think, after an entire lifetime of rebellion and non-conformity, he was finally coaxed back into the Zen fold in 1474, at age 80. The authorities had persuaded him to become head abbot of Daitoku-ji, one of the most important Zen temples in the country. Even now, as an old man with one toe in the grave, he still kept people guessing. Despite appearances, this wasn’t a last minute conversion. If anything, it was a confirmation of the spirit that had pumped through his veins ever since he was a child. The truth is, he had always lived the Zen life—so much so, that the shallowness of his fellow monks was what made him rage against the establishment, not Zen itself. If anything, he was a Zen flag-bearer berating his own people, not as a traitor, but as its greatest patriot. They simply weren’t living up to their own standards. Daitoku-ji, however, had been destroyed in the Ōnin War, and he couldn’t bear to see this symbol of everything he stood for remain a wasteland.

Daito’s descendants have nearly extinguished his light;

After such a long, cold night, the chill will be hard to thaw even with my love songs.

For fifty years, a vagabond in a straw raincoat and hat.

Now I'm mortified as a purple-robed abbot.

One cannot even begin to imagine how false it must have felt to him accepting the position. But as with everything in his life, Ikkyū took to the role with his trademark vigour. Overseeing the temple’s reconstruction, it took seven gruelling years for the complex to be rebuilt. The effort, however, left the old monk completely exhausted, and he finally passed away a short time afterwards seated in the lotus posture at the age of 87.

Not long before his death he had told his disciples: “After I'm gone, some of you will seclude yourselves in the forests and mountains to meditate, while others may drink rice wine and enjoy the company of women. Both kinds of Zen are fine, but if some become professional clerics, babbling about ‘Zen as the Way,’ they are my enemies.”

Indeed, even to the end, he remained the eternal rebel.

In 1457, at the age of 63, he had written,

Writing something

To leave behind

Is yet another kind of dream.

When I awake I know that

There will be no one to read it.

Ah, if only he could have known the future. I wonder, could he have imagined that 565 years later, a recovering drug addict and European heathen might find comfort and inspiration in his magical words? No doubt, his life really was some kind of dream, just as all lives, after some serious thought, are revealed to be dreams, no matter the climate or culture. After all, how could so much beauty and so much suffering co-exist? How could a human life be so delightful and yet so tragic in its trajectory? Like the Stoics had recognised hundreds of years before him, Ikkyū recognised the strange punctuation mark that finalises all life. Death, grinning that toothy grin at man and woman alike. Death, mocking all our vanity, just as the skull Ikkyū brandished one New Year’s Day, mocked all of Kyoto.

Yes, our mortality colours every aspect of our lives whether or not we repress it or express it. On the surface, such claims might appear pessimistic, but how can the truth be considered pessimistic? It is what it is, that’s all. It’s just as the infamous Australian outlaw, Ned Kelly, said before a noose snapped his neck in 1880, “Such is life.”

Yes, yes, such is life.

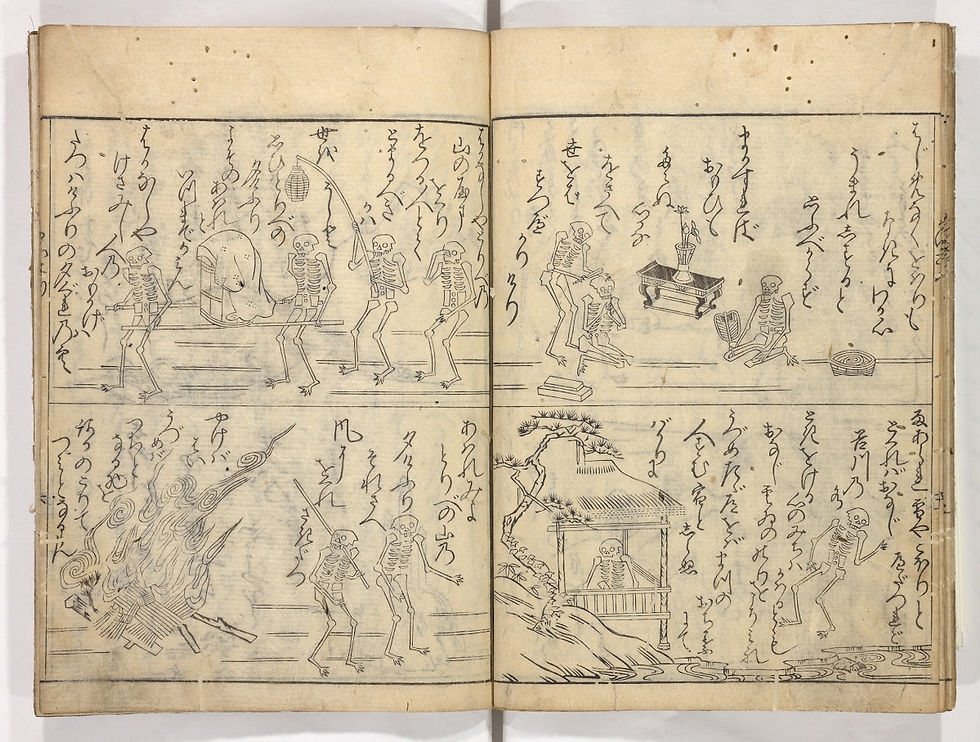

In one of his greatest works, Skeletons—both profound poem and poignant polemic—Ikkyū addressed the topic of death directly. The narrator recounting a dream in which he was surrounded by a group of skeletons behaving as if they were still alive. One of them was even polite enough to approach him and explain a few things,

Still breathing, You feel animated, So a corpse in the field Seems to be something Apart from you. In the same piece, Ikkyū would go on to write,

“What is not a dream? Who will not end up as a skeleton? We appear as skeletons covered with skin—male and female—and lust after each other. When the breath expires, though, the skin ruptures, sex disappears, and there is no more high or low. Underneath the skin of the person we fondle and caress right now is nothing more than a set of bare bones. Think about it—high and low, young and old, male and female, all are the same. Awaken to this one great matter and you will immediately comprehend the meaning of ‘unborn and undying’”.

Not exactly a positive spin on the subject, but undoubtedly an honest one.

Elsewhere, as if summing up his entire life, he would brush the following verse, All is in vain! This morning, A healthy friend; This evening, A wisp of cremation smoke.

Comments